a journal of interesting technical ideas . . .

a journal of interesting technical ideas . . .

Nobody likes change but a baby. That’s the saying anyway. Yet in IT, we have to deal with constant change. Not only that, we have to manage it to minimize risk and harm. And we have to balance the natural tendency to manage through bureaucracy against the need to get things done without paperwork getting in the way.

This article isn’t about why you need change control: you do. It’s not about the value of ITIL or ticketing: they’re necessary. But if you’re going to turn this “computer-thing” into a career, you need to figure out change control and that’s what this article is about.

A lot of my thinking on this topic comes from working with people like Dan and Umesh. These are thoughts that we developed together and made work, and that’s why I feel confident recommending them to you.

Change control documentation needs to layout the change for review. Review is not a second-guessing session, although if you propose something stupid it can be. Good change review is going to make sure that the plan makes sense, that the right people are notified, that there are no conflicts with other IT changes or business requirements, and that the appropriate level of specificity is present in the docs.

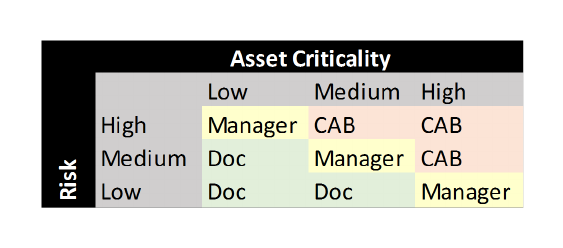

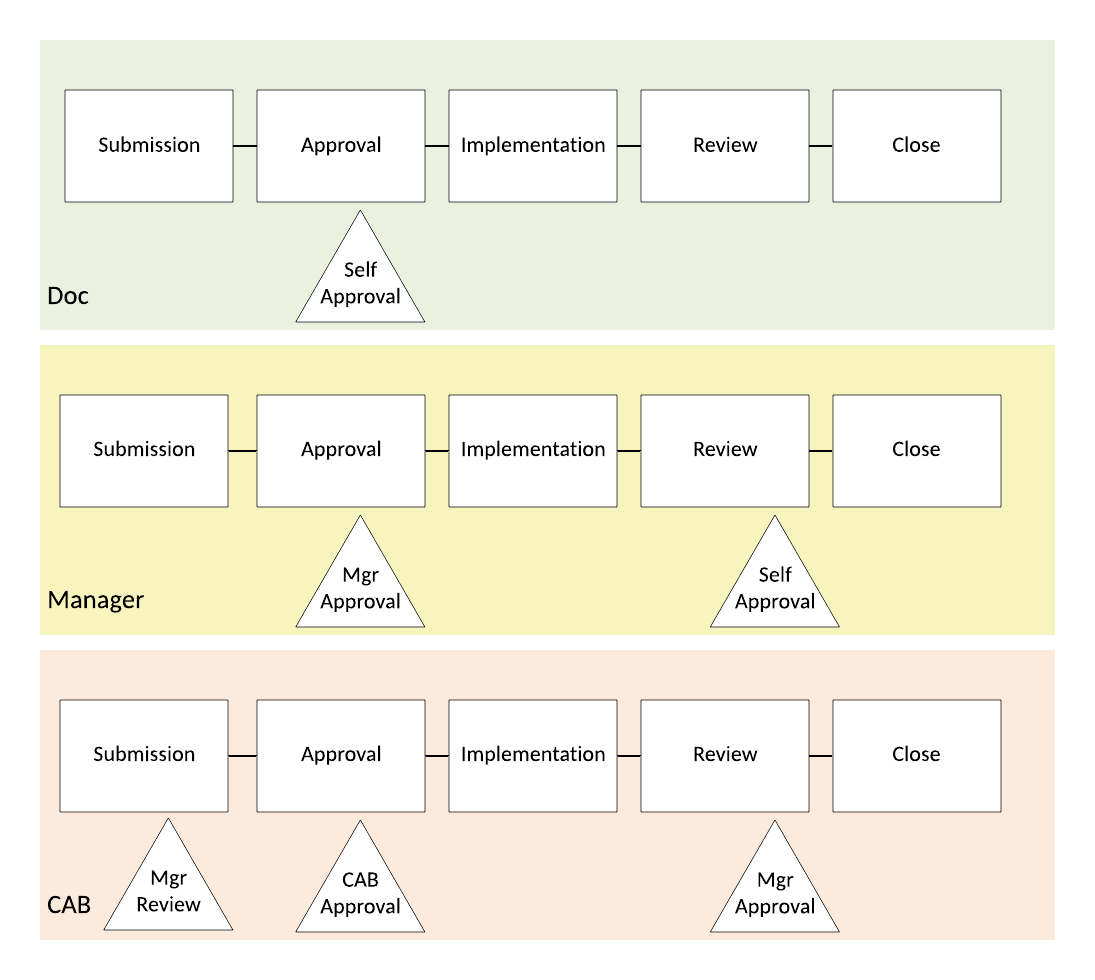

The right level of specificity . . . that sounds tricky. Generally, I’ve found that proposed changes fall into three piles. The easy pile really doesn’t need to be reviewed, it just needs a little documentation. The medium pile needs a little review, perhaps by a manager, and a little more verbiage in the docs. The hard pile needs a lot of careful thought and benefits from a collaborative and thorough review. It needs to be reviewed at several stages, including by a Change Advistory Board.

The table on the left is the one that I’ve developed and used. Changes are described by risk and asset criticality.

Risk – risk is subjective from the perspective of the person performing the change. What is not risky for you might be more risky for me.

• Low – I’ve done this a million times and it always works. There is a redundant system and backout plan.

• Medium – I’ve done this a few times and it usually works. There is a redundant system and backout plan.

• High – I don’t have a lot of experience OR there isn’t a redundant system or backout process that meets the availability budget.

Asset Criticality – This is defined per CI or environment. Availability budget is an SRE concept that specifies the target availability based on budgeting and does not include regular scheduled downtime. The exact AB percentages and how they are measured will change based on the environment, but they might look something like this.

• Low – interruption or loss impact one or a small number of non-critical systems/users at non-critical times

• Medium – interruption or loss impacts ability to conduct business (availability budget >98%)

• High – an interruption or loss of this system would impact clients (availability budget > 99.99%)

Yes, this ranking is a little arbitrary. My experience is that having an overly complicated system leads to folks using the system to justify making changes “less critical”. A simpler system trusts the engineers more and they typically respond to that trust with more conservative assessments. That said, if nothing bad happens then changes will be viewed as less risky over time. One important component is that the CAB needs to review a sample of non-critical changes and push back by calling out some examples of mis-classified changes.

CAB documentation needs the full kit and caboodle and here’s what that looks like:

Purpose: Why is this change necessary? What is being done (in 20 words or less)?

Basics: Who is doing the work? What is the proposed change window? NOTE: I recommend that a change window include recovery time. If that’s not known, I generally allocate 1/3 of the window for the change, 1/3 for the troubleshooting, and 1/3 for backout. In a complicated change, I actually script steps and expected time of completion for each, plus have a hard fail-back moment.

Affected devices (CIs): Which pieces are being changed?

Risk of Change: If we go forward, what’s the worst that could happen?

Risk of NOT making the change: Ah, here’s an important point. In IT there is often risk in making a change, but if you DON’T apply that patch you are vulnerable. If you DON’T upgrade, power supplies fail. Stuff will happen and it’s important to point out that sitting on our hands won’t save us.

Impact: Describe the impact assuming everything goes as planned. For instance, the plan is to upgrade an OS which will require a reboot. Users will at minimum see an impact for minutes while the device reboots.

Details: This section is a breakdown of the steps involved. The level of detail has to be worked out in each organization, but I generally find that it needs to be detailed enough that multiple people familiar with the equipment could read the doc and would interpret it similarly and complete the same steps. Using the exact commands can be good, but it’s best to be a little vague so that a missed detail doesn’t require another change control document.

I like to breakdown the activity into three areas. Pre-downtime and Downtime cover the preparation and the activity during the change window. These steps also need to describe how the change will be tested. Backout Plan talks about steps to be taken if it doesn’t go well. Each of these steps need to include communications - who will be notified and when will they be notified?

In my opinion, CAB level changes should be previewed by the manager to prevent wasting the Boards’ time. The manager should also review the result to ensure it meets the commitment. Less complicated changes don’t need this level of detail. “Medium” changes can usually focus on the details and just be approved by a manager.

Change systems are about organizing people and getting them to talk to one another. They’re also about holding folks accountable for a professional level of forethought. Notice that I didn’t say results - we all recognize that even the best planned and most predictable upgrades can go sideways without it being someone’s fault. But if the right kind of thought process was used, we’re equipped to recognize the problems and correct them, or at least escape unharmed.

Similarly, making sure that the right people are consulted and updated means that these little “oops” moments become events that generate more trust. Imagine a VIP saying, “You told me something might happen, when it did you were prepared for it and kept me in the loop, and harm was minimize because of the thoughtful approach.”

I like to say that a good change process is like a victory lap - all the hard work is done before the change ever starts.